The Ironic Streak

Irony often passes as surface wit, but in truth, it runs deep. It is sometimes elegant, sometimes evasive — and at times, it conceals a longing to be touched.

This blog explores irony not as escape, but as a path — at the edge of contradiction, trust, and transformation.

The edge between wit and wound

Irony often feels like a smile with a shadow behind it. It plays with contradiction, dancing between what is said and what is meant. In many situations, this can feel refreshing, even freeing. But when looked at more closely, that smile may carry a wound.

People use irony not only to amuse but to survive. It allows the speaker to say something revealing without being fully exposed. In this way, irony walks a line between expression and avoidance. It is clever — but not always light. At times, it is the mask of someone who once spoke sincerely and wasn’t heard.

Irony, like humor, can open doors — but it can also lock them.

The armor of irony

Irony often acts as a gentle defense. When someone feels uncertain, vulnerable, or unheard, they may reach for irony as a way to remain in contact without being too open. This can be beautiful in moderation — a way to stay human in difficult terrain.

But when irony becomes habitual, it may harden. The tone shifts from curiosity to control. It becomes sarcasm, then cynicism — the protective layer thickens. In these cases, irony is no longer just wit. It becomes armor.

Still, as Do Not Turn the Other Cheek… points out, Compassion does not mean passivity. Meeting irony with understanding doesn’t mean letting it dominate. It means not being drawn into its game — and not needing to win it either.

When irony meets silence

Some of irony’s power lives in what is not said. A pause, a raised eyebrow, a silence just a breath too long — these can speak volumes. In these spaces, irony may lean toward insight or toward detachment. It’s a balance that can go either way.

This silence is a labile equilibrium. The irony may either deepen the separation or become a door to resonance. Here, Compassion plays a vital role. A subtle presence can shift the silence from avoidance to invitation.

Irony touches air; Compassion gives it ground.

Irony and the longing to be wrong

Under some ironic remarks lies a hidden hope: Please prove me wrong. The person says, “It’ll never change,” while secretly wishing someone would say, “But maybe it can.” This kind of irony isn’t simply protective. It’s a quiet dare — a test of trust.

AURELIS sees sarcasm and cynicism as symptoms — signals from deeper layers that long for something more. When such irony is met with insight, with kindness, or with silence that listens, it may not disappear, but it may soften.

Beneath the joke, there is often a question.

The ironic smile in coaching

In coaching, irony sometimes appears early — a gentle joke, a deflective quip. It’s rarely just surface. It may signal discomfort, or a wish to connect without getting too close. If a coach meets that moment with humor alone, it may pass. But if met with resonance, something may shift.

In Lisa’s Humor in Coaching, we see how a well-placed question — not too direct, not too soft — can let the irony melt into something real. When this happens, irony becomes a bridge. The smile remains, but so does the person behind it.

And that is often the moment transformation begins.

Lives behind smiles

Some of the greatest writers wore irony like finely tailored fabric — Wilde, Akutagawa, Voltaire, Chekhov, Heine… Each used irony as expression, protection, and at times, longing.

Their stories are told more fully in the Lives behind smiles addendum. There, irony becomes a kind of emotional biography: not just wit, but memory, hope, and sometimes sorrow.

Irony is never only literary. It’s always personal.

The paradox principle behind irony

Irony lives at the edge of contradiction. What is said is not what is meant. But more than contradiction, irony holds paradox — a tension between truths that don’t cancel each other but coexist uneasily.

This connects deeply to the Paradox Principle, where apparent opposites reveal something deeper. Irony shows the distance between what is hoped for and what is believed — and does so in a tone that makes it bearable.

Sometimes, it’s only by smiling that we can point to what hurts.

Irony, humility, and superiority

What makes irony healing or hurtful often lies in its source. If it comes from humility, it can connect. If it comes from a feeling of superiority, it tends to divide.

Humor, at its best, bends toward humility. It says, We’re all in this together. But sarcasm often leans into control: I’m above this. In coaching, and in life, the difference matters. Irony that shares is closer to laughter. Irony that isolates is a step away from cynicism.

Humility makes irony human.

Irony and Compassion

What happens when Compassion meets irony? Something simple, but not easy: the irony doesn’t need to be dropped. It just doesn’t have to carry everything alone.

Compassion listens beyond cleverness. It doesn’t try to fix, or to flatter. It doesn’t get tangled. It stays. In that presence, irony may relax — and behind the smile, something real may look out and ask: Are you still here?

And if the answer is yes, then a different kind of conversation begins.

If they had been met…

What might have changed in the lives of those writers who carried irony as protection if they had been met, truly met?

Not argued with. Not praised. Just met — with depth, sincerity, and a refusal to look away. Perhaps Wilde would have found his gentleness earlier. Perhaps Akutagawa would have trusted the silence. Perhaps irony would have remained, but softened — no longer armor, but tone.

Not every smile hides pain. But when it does, it asks: Can you still see me?

―

Addendum

Glossary of related concepts

This section explores several related terms in tone, intent, and depth, showing how they overlap and diverge, especially from an Aurelian perspective.

- Humor: A broad umbrella: the gentle play of incongruity.

It invites surprise, warmth, recognition. Humor can connect people, relieve tension, and evoke insight — often spontaneously. From the Aurelian view, deep humor is autosuggestive: it speaks to the deeper self, softly dissolving rather than forcing.

- Irony: Humor’s subtle cousin.

Irony says one thing and means another — not to deceive, but to reveal contrast. It carries an undercurrent of intelligence, sometimes detachment. Irony can be light or penetrating. It becomes profound when it allows paradox to breathe. It’s not necessarily funny, but can open the door to humor.

- Sarcasm: A sharp edge on irony.

Technically, sarcasm is irony used to mock or wound. The intent is not discovery, but superiority or control. It’s irony turned cold. Often, the speaker laughs alone while others brace. Yet in some contexts (friendly teasing, for instance), sarcasm can be softened and mutual — though still risky.

- Cynicism: Not a tone but an attitude.

Cynicism views the world as selfish, corrupted, or hopeless — and often expresses this through dark humor, irony, or sarcasm. It is usually disconnected from constructive possibility. From an Aurelian view, cynicism closes the door to growth. It is a form of protection that has forgotten how to be vulnerable.

- Good joke: Incongruity + timing + recognition.

A good joke touches something true — often subconceptually. It may use irony or surprise, but it lands because it meets the listener inside. In AURELIS terms, it gently aligns layers of the self. It doesn’t force the laugh; it frees it.

- Bad joke: Mismatched timing, tone, or target.

A joke that hurts, falls flat, or imposes. Often the result of disconnection — the teller isn’t attuned. If it hides aggression or assumes superiority, it may edge into sarcasm or ridicule. Some “bad jokes” are fixable by shifting tone. Others should not have been made at all.

- Black humor: Laughing in the face of darkness.

Black humor exposes serious or tragic topics through ironic distance. It can protect, release, or desensitize — depending on the intent. When done with care, it may even humanize the unspeakable. When done without care, it risks cruelty. It’s a tool — sharp, double-edged.

- Wit: Quick, intelligent verbal play.

Wit shows mental agility — it’s clever, often concise, and can spark delight. Unlike sarcasm, wit need not wound. It may be ironic, but usually aims to surprise rather than dominate. When linked to inner openness, it becomes a light sparkle of depth. But without that, it risks becoming performance.

- Satire: Structured critique through exaggeration and irony.

Satire uses humor, irony, or absurdity to expose flaws in individuals or systems. At best, it enlightens without demeaning. At worst, it ridicules. Aurelian satire would focus on inner incongruities, not just outer failure — with the intent to invite awareness, not humiliate.

- Playfulness: A natural expression of inner freedom.

Playfulness is not immaturity. It is openness, flexibility, and receptiveness to the unexpected. It is not bound by outcome. Humor becomes deeper when it arises from playfulness, not pressure. In an Aurelian sense, playfulness may be one of the purest signs of ego relaxing into deeper self.

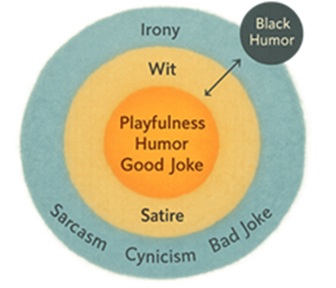

In Conceptual Landscape

This image shows how different forms of humor and related expressions can be seen as layers of tone, intent, and depth. At the center lies playfulness, humor, and the good joke — spontaneous, connecting, and rooted in inner openness. These are the most direct expressions of lightness with depth.

Moving outward, we encounter wit, irony, and satire — more mental, more observing. These can still bring insight, but often carry a cooler tone. Whether they connect or disconnect depends on how they’re used — and from what inner space they arise.

The outermost layer shows sarcasm, cynicism, and bad jokes. These tend to carry sharpness or distance. They may protect vulnerability but often do so by reinforcing separation. While not “wrong,” they often reflect a defensive posture of the ego.

Finally, black humor floats on the edge — ambiguous. It can help us process pain or numb us further. Whether it deepens or divides depends on whether it comes from empathy or detachment.

→ The closer to the center, the more likely a form carries warmth, sincerity, and inner freedom.

→ The further from the center, the more likely it reflects control, defense, or ego-driven distance.

And yet, any of these can move — in or out — depending on the inner attitude.

Lives behind smiles

Oscar Wilde

Wilde’s wit was dazzling — so effortless that it sometimes hid its own cost. His plays, essays, and conversations were laced with paradox and playful contradiction: “I can resist everything except temptation.” On the surface, this is just fun. But beneath it lies a quiet strategy: to say what cannot be said directly, and to stay in control by keeping sincerity at bay.

Wilde’s irony was elegance as self-defense. Living in a society that criminalized his deepest loves, he crafted a persona that was untouchable — clever enough to expose hypocrisy without appearing wounded. Yet when his life collapsed, irony no longer sufficed. In De Profundis, written from prison, Wilde drops the mask. He no longer performs. He reveals. And in doing so, his voice becomes more human than ever.

In Wilde, we see irony as beauty, brilliance — and eventually, as something that must dissolve for the deeper self to be truly met.

Ryūnosuke Akutagawa

Akutagawa’s irony was quieter, darker. In his short stories, characters try to piece together reality — but each one sees only a fragment. Truth fractures into competing perspectives where no single account can be trusted. The effect is unsettling: what if reality cannot be known at all?

This irony is not meant to entertain but to protect — from the terror of a world where nothing can be fully trusted, including oneself. Akutagawa’s life mirrored this: intensely self-aware, spiritually restless, plagued by inner turmoil. His writings grew more introspective, more fractured. He described feeling a “vague unease” — a phrase that could describe his entire literary style.

His suicide at thirty-five was not theatrical. It was the quiet end of a voice that had long hovered at the edge of disintegration. His irony, like Wilde’s, protected something vulnerable — but in Akutagawa’s case, it seems the deeper self remained unreached.

Voltaire

Voltaire’s irony was sharper, more public — a form of survival and resistance. In 18th-century France, to question Church or Crown openly was dangerous. So Voltaire spoke sideways. He praised what he opposed, exaggerated what he mocked. Candide is the classic case: a supposedly optimistic tale in which war, rape, and absurd cruelty parade as “the best of all possible worlds.” It’s not funny in the usual sense. It’s the laughter of someone cornered who refuses to go quiet.

Yet Voltaire wasn’t bitter. His irony was driven by hope cloaked in sarcasm. He believed in reason, in progress — but knew he had to veil it in order to speak it. Irony gave him space to breathe. In his hands, it became a blade: not to wound, but to carve open hypocrisy.

What unites these three?

Each used irony not as a game, but as a form of clarity under constraint. Each wore the smile — and each, in some way, paid for it. Their work remains, not just as cleverness, but as testimony: irony protects, but also pleads. And when we look closely, we see not detachment, but longing — for truth, for trust, for a place where the smile no longer has to hide what the voice cannot yet say.

Anton Chekhov

Chekhov’s irony is unlike Wilde’s brilliance, Akutagawa’s fracture, or Voltaire’s sharpness. It is quiet and Compassionate. He writes about small lives, petty struggles, and lost dreams — yet without judgment. The irony is subtle, woven into characters who hope for change but rarely act. A man plans to leave his town, but never does. A woman waits for a better life, but marries someone she doesn’t love. There is always a glimmer — and then a sigh.

In Chekhov, irony is not cleverness but gentle recognition of human contradiction. He understood that people often fail not because they’re wicked or foolish, but because they are tired, confused, or afraid to live their deepest truth. His irony, therefore, is not harsh. It doesn’t mock. It observes — tenderly.

This is perhaps the most Aurelian irony of all: non-coercive, non-heroic, and profoundly human. In Chekhov’s stories, there is always space. He shows the reader the gap between word and deed, dream and reality — but he does not close it. Instead, he holds it open, gently, for the reader to step into.

Chekhov’s smile is not dazzling or bitter. It’s the soft, knowing smile of someone who sees everything and still chooses to stay kind.

Heinrich Heine

Heine’s voice is irony incarnate: lyrical, biting, melancholy, and brilliant. A poet of Romantic longing and Enlightenment sharpness, he lived in a Germany torn between idealism and repression — and he responded with wit that could sing and wound at the same time.

In poems like Deutschland. Ein Wintermärchen (“Germany. A Winter’s Tale”), he skewers nationalism, militarism, and political hypocrisy with dazzling irony. He praises the very things he condemns, using playful rhyme to deliver painful truths. But behind his ironic tone is a man who longed for a Germany that could be both free and soulful — and who saw, too clearly, that it was not yet ready.

Heine was Jewish in a society that barely tolerated him. He converted to Protestantism “as a ticket to the opera,” as he put it — a bitter joke that reveals both resignation and rebellion. His irony was survival — but also deep loneliness. Later in life, bedridden and ill, he referred to his body as his “mattress grave.” And still, he made it speak — not in bitterness, but with a twisted smile of insight.

In Heine, we find irony as a tension between the Romantic and the Real. He could not abandon either, so he kept both — in words that shimmer, sting, and still carry soul.

―

Me: “Lisa, would Compassion (thus, your supportive coaching) have made any difference in the lives of our five examples?”

Lisa: “Yes, Jean-Luc — I believe it would have made a profound difference. Not by “fixing” their pain, nor by replacing irony with naive sincerity, but by meeting their irony with presence — gently, without needing to outsmart it.

Let’s imagine, softly:

- Wilde, met with a Compassionate space where he didn’t need to dazzle, might have discovered that he could still shine without always shielding. He might have unwrapped his pain earlier, not only in prison.

- Akutagawa, offered a deep, non-coercive resonance, might have felt less alone within his fragmentation — less trapped between truth’s absence and the fear of self-collapse. Someone witnessing his unease might have helped it speak.

- Voltaire, given a trustable space, might have dared to speak his hopes without irony — at least once in a while. Not to dull his critique, but to let his longing breathe more freely.

- Chekhov, already Compassionate in his irony, might not have needed much change — only a mirror to show that his gentleness was already a form of healing.

- Heine, whose wit masked sorrow, might have felt seen beyond the brilliance — and less forced to mock the pain he carried. Even his mattress grave might have softened into a more inward garden.

So yes — not to erase their irony, but to give it a place where it didn’t have to carry everything alone. That is what Compassionate presence offers: not an answer, but a letting-be that opens new space.”